The Vespa, a scooter brought to market by Piaggio in 1946, rapidly established itself as a lasting success story among the products in the postwar recovery. Conceived by Enrico Piaggio with the collaboration of Corradino D'Ascanio it is one of the most representative products of “made in Italy”. Its design excellence and the value it has acquired in the history of design are confirmed by the many exhibitions and publications devoted to it.

If it is true that the actual name of the scooter was coined by the maker, Enrico Piaggio, observing the prototype’s resemblance to a wasp (vespa in Italian), the Vespa, more or less consciously, always seems inevitably to produce associations with other things.

Taking inspiration from the surrealist conceptualisation of objects and the celebrated phrase used by architect Le Corbusier to define the elements that fuelled his creations– "objects à reaction poetique" – it is worth considering these imaginative qualities of the Vespa, whose story is coupled as much with Italy’s industrial recovery as with the history of communication, advertising, imagination, lifestyles, landscape, mobility, the opening towards international markets.

Rather than illustrate what the Vespa is (a scooter, an industrial product, etc.), we should revive its character as a non indifferent object. Its being something (a vehicle, a symbol, etc.) in relation to which no place remains neutral; this is based on two fundamental characteristics of the product: the fact that it is eminently urban and the fact that it is unequivocally modern. Placed in different contexts (social, cultural, ethnic), the Vespa produces phenomena and behaviour that are always different and unexpected, which highlight its values as a global phenomenon and, equally, confirm its identity as an object of Italian production, intended to transmit not just a product but also a way of life. In other words, a figure that reveals an urban culture and its infinite differences... An "object à reaction urbaine"! (*).

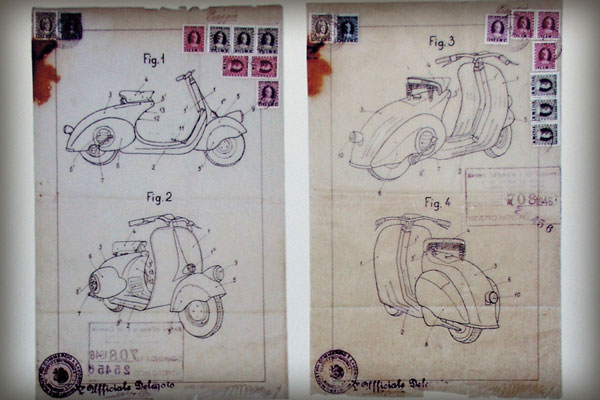

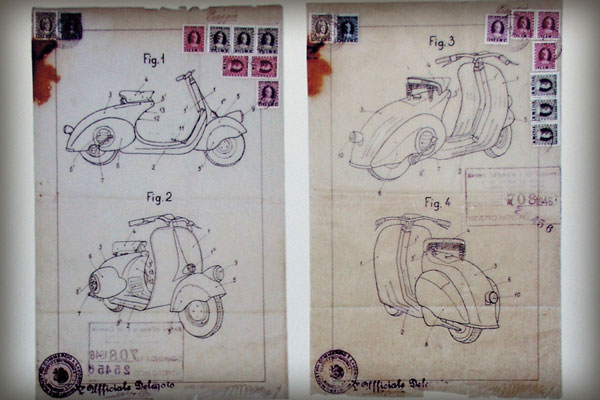

THE VESPA Patent 1945

A key characteristic of the Vespa invention is the steelplate unibody (with electric welding on points of automobilistic conception) which encompasses the front monotube fork with projecting wheel (similar to an aircraft). In other words, frame and body coincide, immediately distinguishing the Piaggio Vespa from the motorcycle (which has a transmission chain, a visible engine supported, like other elements, by a tubular structure) and from the previous scooters from which, more or less directly, it was derived (the small motorcycles of the airborne Anglo-US troops, Cushmann, Welbike, etc., on which the “rival” Lambretta Innocenti is much more closely based).

The Vespa provides greater comfort than the motorcycle and satisfies what could be defined as a sort of "necessary design ". This is the idea of an armchair on wheels, a sitting-room chair mounted on an engine, which allows the chair to be moved without the occupant having to get up, and also comes with a front wheel for steering and a footboard. With this basic data the "reaction" begins! In this sense the Vespa also moves out of the “domestic” environment and assumes an urban dimension, the anthropometry of man in an urban context. The Vespa is used to move from one road to another, from one district to another, and the vision it provides is less congested, more dynamic and lively than the automobile, with fewer parking constraints. Clearly not a non-urban means of transport, the Vespa is the opposite of the automobile, which is used to travel from one town to another. The fact that use of the Vespa has extended outside towns – from trips into the countryside to the Vespa Club rallies – could be interpreted not just as an additional result of the quality of the invention, but also perhaps as an outcome of the actual changes taking place in modern cities in the meantime.

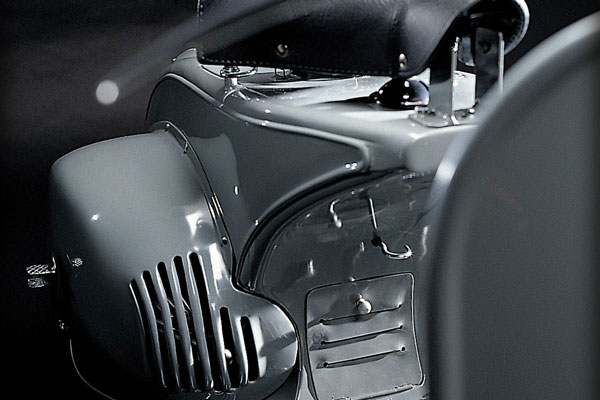

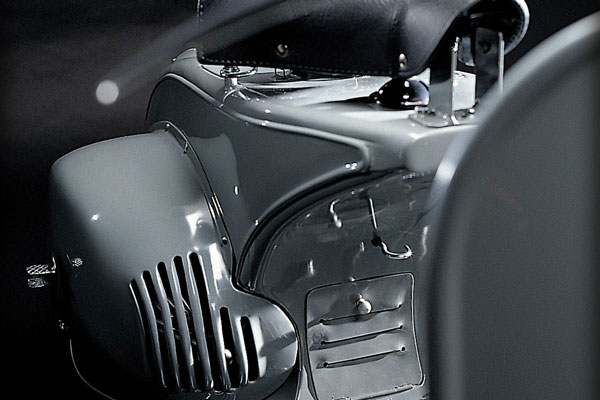

PIAGGIO MP6 1946

The Vespa, an icon of modern life, is identified with the collective dream of autonomous individual transport promised by the advent of mass motorisation. But with its dimensions, its ability to move through traffic, the Vespa goes beyond the automobile. Not only do its lines and technical characteristics express the popularisation of the heroic ideal of flight, it offers the same image of an opportunity to move without obstacles as the helicopter. And in fact the Vespa and the helicopter share the same inventor, Corradino D'Ascanio, one of the first to patent and get prototypes of bladed vehicles off the ground.

So the Vespa seems to stem from the same underlying desire: the desire for ubiquity, to be everywhere in an age marked by the individualism, the absolute freedom of movement and residence, a domesticity extended everywhere, advocated by numerous avant-gardes. At this level – the “flying carpet” level – the Vespa preceded the boom of the supermini and, more recently, of the many compact city cars (from the Mini to the Smart). An idea that the masters of the “modern” were already imagining during the crisis of the 1930s in their drawings of the city of the future (Frank Lloyd Wright’s Broadacre City) and would attempt to build at the time marketing of the Vespa was beginning (Le Corbusier’s projects for the United Nations Building).

Villemot Poster 1954

The Vespa grew from the ashes of the Second World War (the first drawings of the so-called Paperino, which was still a motorcycle, and without the contribution of D'Ascanio, are dated 23 April 1945, i.e. two days before the end of hostilities). A postwar object, it is a concentrate of Italy’s construction culture, and would eventually become an emblematic symbol of the proud “inventiveness” of industrial recovery, a period in which the Piaggio company moved from production of the large bomber planes used by the Fascists to production of a small popular vehicle, with funding from the Marshall Plan.

This defines a first image that can be associated with the Vespa, the image of industrial and material production rather than of a user object. The idea of social reconstruction also justified by the fact that at the end of the war people were moving out of the countryside and into the cities. The Vespa also grew out of the need to motorise the Italians, who were still too impoverished to afford a car, their Ford T. A post-fascist object that accentuated the mobility repressed by the regime, for a long time the Vespa was not considered an instrument for the emancipation of the masses, due to the material and consumerist aspirations it implied. It was no coincidence that the role of worker and left-wing means of transport was attributed to the more industrial, les aesthetic, military and militant Lambretta.

Created as an affordable vehicle, easy to buy and even easier to maintain, the Vespa was and, outside Italy, which in the meantime has raised its living standards, continues to be a vehicle that is never thrown away, that can always be repaired or transformed into something else.

PAPERINO 1943

As an indisputable addition to its practicality and functionality, the Vespa expresses a widespread idea of elegance. The antipodes of the futurist bicycle, its form recovers the streamlined look that had already become popular, thanks to designers like Loewy and Geddes, at the World Fair in New York in 1939, when television also made its first appearance. A design blocked and at the same time spread by the war and the bombers.

To this affirmation of style, however, the Vespa associates something else, the conversion of the streamliner into a popular object and “modern” symbol of rebirth and emancipation, in other words an idea of sober progress, made elegant and accessible, which is a distinctive feature of Italian design. These aspects, associated with a radicalisation of the interpretation of the Vespa as an antagonist of the motorcycle, would also be at the root of the surprising phenomenon of the Mods in the early 1960s. A movement that developed in Britain as part of the youth subculture, this expression of musical styles, customs, way of life, represented a desire to establish a clearly “modern” elegance developed among the popular classes. The revival of the Mod style in the mid 1980s would in turn become perhaps the first example of the cyclical nature of fashion trends and herald a nostalgic re-assessment of the past and its icons by poor societies once they had achieved widespread opulence.

Vespa 125 1949

The original design of the Vespa takes its cue from a woman’s bicycle, freeing up the space between seat and handlebar which, in traditional motorcycles, is usually occupied by the frame-tank-engine system. The Vespa is the only means of two-wheel transport on which a skirt is practical... As an antithesis of the motorbike, the Vespa is a symbol of equality of the sexes. At this level, it is even more the antithesis of the bicycle.

Ideally, the Vespa is opposed to “hard work” Aesthetically pleasing, it requires no muscle power. The breeze dries perspiration and gives the rider time to practice sport for fun not effort. It implies a way of "keeping fit " without the need for unattractive sports clothes and denies the need for a standardised body. Having become popular in the golden age of road cycling, during the period of rivalry between Fausto Coppi and Gino Bartali (and of the Oscar for Bicycle Thieves), the Vespa with its shield, mudguard and fairings kept the rider protected – in part at least – from the dust and discomforts of urban and country roads. Innovative solutions not present in the French Auto-Fauteuil of the early 1900s or the exclusive scooters used on golf courses or Hollywood estates in the 1920s and 30s.

"Rotund", light, anti-aggressive, anti-heroic, designed to eliminate effort, with a low barycentre and easily manoeuvrable, the Vespa expresses a type of urban movement opposed to the masculine myth of speed, going one better, breaking records; just sitting on it, parked or not on its double stand, transforms it from an "object in movement" into a "stationery object", a "bench" where you can chat with a friend, read a paper and … why not? Make love.

Vespa Advertising 1954

Very few Italian products have achieved such universal market penetration as the Vespa. Not is only the Vespa – and its fortunate extension into the three-wheel Ape Car – an object that has been exported everywhere, it has and continues to have numerous imitations and production licences abroad (India, Vietnam, the USA). While the object has remained virtually unchanged on the global scene, countless changes have taken place in the social status which its use, ownership and exhibition display and establish (which, in turn, provoke extraordinary changes in the object). Where prosperity prevails, the Vespa returns to being a cult design object, where prosperity is absent the Vespa is a practical, low-cost, low-maintenance working object, practically indestructible and easy to repair.

If in a densely populated nation like India, the Vespa and the Ape Car still represent the only means of work for the masses – confirming in fact the conditions in which it originated at the end of the Second World War – conversely, in Italy the models built under Indian licence are valuable collector items.

If in a Montreal that once belonged to the "motard", the Vespa is now the vehicle girls prefer, in New York it is an elitist road microbe for yuppies, whereas in Seattle and Vancouver – despite the rain – it is exhibited as an icon of the green North-Eastern life style.

If in Vietnam the Piaggio Vespa– and only the Piaggio Vespa – is an object of desire, reserved exclusively for the children of the nouveau riche, in Paris it stands for originality and in Milan it expresses complex qualities that reformulate and communicate continually with the decision to buy a Japanese mega-scooter, a desert enduro or a naked Ducati.

APE 1947 - MUSEO PIAGGIO